|

Program Notes

Recording companies often seize upon a single aspect of their records for promotion: a composer who has suddenly become fashionable; a piece of music re-discovered; a performer who has caught the public's fancy. But every so often, a record appears in which each element is of so fine a quality, that the whole is clearly destined to become a classic. Such a record is within this jacket.

First, the music is some of the most electrifying "whirlwind music" composed for the organ. Second, it is played by America's most popular concert organist, Virgil Fox, in a performance that will forever be a classic example of great virtuoso technique combined with superlative musicianship. Third, the organ is one of the first and finest examples of perhaps this country's greatest organ builder, G. Donald Harrison. Fourth, the room, Symphony Hall, Boston, is perhaps the most distinguished concert hall in America; its acoustics, simply stated, are ideal. And fifth, Command's recording techniques have reproduced a sound that is unsurpassed in musical, as well as acoustical fidelity.

Virgil Fox, almost single-handedly, has been creating interest in the pipe organ by proving that when the instrument is built musically and played imaginatively, it can generate more excitement than any other solo instrument. And since the building of the Organ at Symphony Hall, Boston, new instruments have been retrieving the sound of the organ from the excesses into which it had fallen: the tubby bombast of convention hall organs and the ugly stridency of recreated museum-piece instruments.

The pipe organ, not long ago, was a hugely popular instrument in America. Yet, its popularity was a short-lived, unhealthy fever; and the disease from which it suffered was "organ grandomania": a fascination with the build-up of sound made possible by the invention of the electric blower.

Certainly one part of the organ's thrill is the massiveness of its sound; but another part must be the beauty of its tone. The pipe organ fell from grace because the increased wind pressure (which the electric blower made possible) blew away precious overtones that had been experimentally developed over hundreds of years. These overtones were the extra frequencies whose presence or absence, for example, distinguishes a Stradivarius violin from a home-made fiddle. The new organ (called the "orchestral organ" because many of its "stops" imitated orchestral sounds) was much louder than its predecessors, but it wasn't particularly beautiful.

A few exceptions should be noted: particularly, the John Wanamaker Organ in Philadelphia (of which Command Records has made a definitive recording). It was one of the largest and certainly one of the finest orchestral organs built in America. Most of the others, however, were mediocre "tubs" that sent little more into the audience than massive volumes of sound.

By 1950, two main reactions against "organ grandomania" had taken place. Each put forth the following ideas: first, a decrease in wind pressure, to recapture the overtones that produce beautiful, clear sound; second, "classic voicing," to give each rank of pipes its authentically characteristic sound; and third, the creation of the "ensemble," which replaces a multi-plicity of individual (orchestral) sounds with a series of ranks that constitute harmonics of the same (organ) sound: an old idea, based on the same principle a composer uses who adds the sounds of the violas and cellos to that of the violin parts, in order to add additional resonance to the "string ensemble" of the orchestra.

The first of these reactions (and, until recently, the most fashionable, within the organ world) produced the so-called "Baroque" organ: a latter-day version of an instrument that was popular several hundred years ago. Basing its theory on the romantic principle that "the past is better," the baroque movement discarded all post-Bach mechanical innovations (with the interesting exception of the electrical blower, which had caused the trou-ble in the first place) and created an instrument of historical interest, but one that, because of its built-in limitations, was difficult for an organ virtuoso to play. Although some neo-baroque instruments have produced quite beautiful tones, the pseudo-sacred "principles of the past" have also been known to produce some pipe organs with remarkably ugly (albeit "authentic"!) sound.

The second reaction to grandomania was the invention of the "American Classic Organ," conceived by G. Donald Harrison, originally of the Willis Organ Company of England, and later of the Aeolian-Skinner Company of Boston. Since his death, Harrison has not been replaced as a master builder of organs; and the Organ of Symphony Hall, Boston, was one of the earliest examples of his American Classic Organ. It is still one of his finest.

Harrison's idea was to build an instrument which, based on the principles of low wind pressure, classic voicing, ensembles and the use of mechanical innovations, could play the organ literature of every country authentically. If one reads the specifications of the Organ at Symphony Hall, Boston, one recognizes German, French, English and Italian stop names, as well as mechanical innovations developed in America.

One can debate whether Harrison achieved his goal of creating an organ that plays all of the literature "authentically"; yet there can be no argument about the success of the instrument recorded in this album: it is one of the finest organs in America. It is an instrument that stands at the beginning of a renaissance; one that speaks with remarkable clarity and with all the authoritative strength of its youth. It is a perfectly formed instrument, and one that bears none of the conceits of old age.

The organ in Symphony Hall, Boston, was built in 1950 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the hall; it is the third organ to play with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the original organ being the first concert organ to play in America.

There are 4,662 pipes in six divisions of the organ. They are controlled from a movable, four-manual console.

The organ's placement is ideal: five of the six divisions of the organ are stretched out, the full width of the stage, flat against the back wall, so that virtually every pipe speaks directly to the audience. (The choir division extends to the right of the stage.)

The low pedal pipes (those that "shake the building") take up the left side of the stage. This placement makes no difference in the hall, since the lowest bass tones are non-directional; but it complicates a stereo recording, because the result (especially on earphones) could be disconcertingly lop-sided. To compensate for the placement, the organ was recorded in the fol-lowing way: Three-track, half-inch tape was used to record the left, right and center sections of the organ. Before mixing these three channels into two, the center and left channels of the original tape were reversed, so that the Positiv, Great and Swell divisions of the organ (in the middle of the stage) are heard on the "left" stereo channel, while the low Pedal Organ pipes are balanced equally between the left and right stereo channels of the record. The "right" channel remains the same, recording the upper pedal work, the Bombarde and the Choir divisions of the organ.

Fantasy in F Minor, K. 608, composed in 1791 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791).

Curious musical inventions, such as music boxes and glass harmonicas, were as fashionable in Mozart's time as the orchestral organ used to be in ours. In fact, they were so much more fashionable than the pipe organ (which Mozart truly loved) and brought in so much more money, that Mozart, who was always short of funds, composed almost as much for these musical novelties as he did for the organ. The Fantasy in F Minor was composed for a mechanical organ that was controlled by an internal clock mechanism. Mozart liked the piece much more than he liked the nobleman who paid for it—Count Deym, whom Mozart considered little more than a philistine collector of curiosities—but he died nine months after composing it and had no chance to transcribe it for the organ. The pedal part, therefore, has been interpolated, over the years, by various music editors.

The work is a great virtuoso piece. The majestic flourishes (called ritornelli) that form transitions between its three sections (Allegro, Andante and Allegro) are all composed in different orders of different chords, as well as in different keys. In other words, the music is as difficult to memorize as it is to play!

Final in B-Flat, opus 21, composed in 1862 by Cesar Franck (1822-1890).

Musical notation is only partly successful in transcribing a composer's intention, and so the performer who "reads" music literally often disregards an essential ingredient on which many composers depend: the performer's interpretation.

It would fascinate most listeners to see a demonstration of Virgil Fox playing the Final in B-Flat exactly as it is written, and then to compare it with the performance on this record. The music, played exactly as written, simply doesn't come off (as, say, the works of Bach usually do, no matter how uninterestingly they are played). The Final in B-Flat comes to life only in the hands of a virtuoso performer.

The listener can understand, somewhat, the difference between Franck's writing and Virgil Fox's rhythmical interpretation of it, if he will imagine humming the opening pedal passages, for example, at half their recorded speed and with no breathing spaces between the phrases. Virgil Fox's interpretation, it will be seen, takes full advantage of his innate rhythmical drive.

The freedom to use such a technique in the performance of Franck's music was shown to him by Louis Robert, a student of French organ music, whose training stemmed directly from Franck. We cannot prove that Franck intended the music to be performed exactly in this manner; but if he did, he need not have written it any differently.

We must note, also, that the music was dedicated to Louis James Lefebure-Wely (1817-1869), a virtuoso organist of Paris, and a composer remembered for his dazzling (though superficial) music. Franck certainly could never have intended the piece to be played with less than a virtuoso technique.

The Final in B-Flat is the last of Six Pieces d'Orgue, which represent the earliest, serious attempts Franck made to compose organ music. Musicologists have rated it as the least successful of the six; yet one cannot doubt that Virgil Fox's performance not only brings it to life, but carries the listener to a whirlwind conclusion as effectively as can any of the works of Bach.

Surely, then, this recording (one of the only recorded performances of the Final in B-Flat) will alter a small piece of musical history, by forcing musical criticism to re-assess a neglected, but worthy, piece of music.

Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, opus 65, composed in 1844 by Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847).

Judging from the publisher's advertisement for the Six Sonatas for Organ, of which this one is the first, Mendelssohn was extremely interested in re-establishing the organ as a virtuoso instrument. Most organists at that time were stodgy players who performed undistinguished music. And after Bach's death (and until Mendelssohn), almost no great music had been written for the organ; and few organists even played the works of Bach!

Mendelssohn must have been pleased, then, when the organists of England, who had heard him play during one of his triumphal tours of their country, were so impressed with his accomplishment as an organist, that they asked him to compose for their instrument. It wasn't until several years later, however, that he accepted a commission from an English publishing house to compose several "voluntaries" for the organ. Mendelssohn composed these, but asked that they be called "sonatas," since he didn't know exactly what the word voluntary meant.

One can find many evidences of Mendelssohn's concern for the virtuoso organ throughout the Sonata No. 1. In the first movement (Allegro moderato e serioso), one hears great contrasts of sound which are formed by doubly-loud (allegro) passages alternating with doubly-soft (serioso) passages. The soft passages are statements of the German chorale Was Gott will, das g'scheh allzeit (literally: What God wills, it at all times happens) upon which the sonata is based.

The second movement (Adagio) stands alone as a piece that is included in almost every compilation of organ works. (The whole Sonata No. 1, in fact, among organists, is almost as famous as the old-war horse, the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor of Bach.)

The third movement (Andante recitando) repeats the alternations of loud and soft of the first movement—a technique that requires great resourcefulness of registration from the organist.

And the final movement (Allegro assai vivace) introduces virtuoso techniques such as had never been heard before on the organ: arpeggios that had been previously played only on the piano, and pedal passages that were completely new innovations. In fact, the closing pedal cadenza is so incredibly difficult, one might imagine it was because Mendelssohn thought the public would never believe its eyes and ears that he included it twice!

|

|

|

|

Original Cover - Select image to enlarge

|

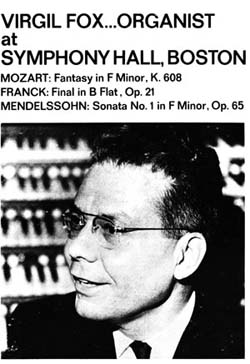

Virgil Fox grew up in Princeton, Illinois. At the age of ten, he already was playing church services on the organ; and at fourteen, he played his first recital before a cheering crowd of 2,500 people in Cincinnati. At seventeen, he was unanimously chosen the first organist to win the Biennial Contest of the National Federation of Music Clubs, in Boston.

After graduating as salutatorian of his high school class, he studied for a year with the great teacher of the organ works of Bach, Wilhelm Middelschulte, and won the top scholarship to the oldest music conservatory in America, the Peabody, in Baltimore. In his twentieth year he played five recitals from memory, completed eighteen examinations with the highest grades in his class, and became the first one-year student in the history of the school to graduate with the conservatory's highest honor—the Artist's Diploma. Six years later, Mr. Fox returned to the Peabody to become the head of the organ department.

Before he did, he went to Europe for a year to study with Marcel Dupre, and to give his European debut at Kingsway Hall in London before 1,100 people, including Britain's most demanding critics. And when he returned to the United States with rave notices, he played his first rectal in New York City at the console of the same 200-rank organ on which Vierne, Bossi and Karg-Elert had played their New York debuts—the Wanamaker Auditorium Organ. He was twenty-one.

Immediately after being discharged from the Army Air Force in 1946, Virgil Fox performed forty-four major organ works from memory in a series of three concerts, given under the auspices of The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation, before sold-out audiences in the Library of Congress. In the same year, he was selected to be the organist of New York City's famed Riverside Church—the church established from the gifts of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and from whose pulpit Harry Emerson Fosdick preached.

Virgil Fox was organist of the Riverside Church for nineteen years. In 1955, following specifications which Mr. Fox drew up, G. Donald Harrison (builder of the Organ in Symphony Hall, Boston) designed and built the largest pipe organ in New York City for the church, a 141-rank Aeolian-Skinner organ, of which Command Records has made the definitive recording (on 35 mm film): Virgil Fox at the Riverside Church Organ Plays Johann Sebastian Bach.

Mr. Fox has played three times in the White House. In 1952, he was chosen by the State Department to represent our country at the First International Conference of Sacred Music, in Bern, Switzerland. In 1963, he was awarded an honorary doctor's degree by Bucknell University. And in 1964, he received the Peabody Conservatory's Distinguished Alumni Award.

In his long and brilliant career, Virgil Fox has given recitals on practically every important organ in the world. He is the only non-German who has ever been invited to play at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig (the church where Johann Sebastian Bach was organist). He has played at the Domkirche (the Kaiser's church), at Canterbury Cathedral, Westminster Abbey and at Notre Dame de Paris. He played the first solo organ recital and made, incidentally, the premier recording on the new Aeolian-Skinner organ in New York's Philharmonic Hall. (Hear, on Command Records, Virgil Fox Plays the Philharmonic Hall Organ at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.)

|